We are not lying when we affirm that there is a certain weariness and saturation of Picasso after the avalanche of quotations on the 50th anniversary of his death. There is no eyelash, eyelash or bunion of his "Andalusian feet" (the category is Fernande Olivier's, to which we will soon return) that has not ceased to be examined, scrutinized and reread in this 2023 celebration. And yet, the great money-making machine that is Pablo Picasso continues to show good health (just look at the latest auction of 'Woman with a watch': 128 million euros). Up to fifty major international events and events, mainly on both sides of the Pyrenees, but also in Europe and the U.S., has given rise to the program of this Picasso Year. Without going too far away, while in Madrid the last of them is presented in the form of an exhibition at the Reina Sofia, in the city there are 'Picasso events' at the Thyssen Museum and La Casa Encendida.

The final bang

For all these reasons, there is little room for surprise left for the last cartridge, which, on the other hand, is expected to be the grand finale, a proposal that proves that it has been worth the wait. The good news is that all these circumstances surround the presentation and display of 'Picasso. 1906. The Great Transformation', as I say, inaugurated this week at the Reina Sofia with Eugenio Carmona as curator. Just the complicity of the Picasso Museum in Paris and the great international loans (from the MoMA, the Metropolitan, the Louvre or the Pompidou, to name a few) is worth the visit to the halls of the center directed by Manuel Segade, where Picasso's decisive works cross paths with others by Corot, El Greco, Cezanne; also with examples of Iberian art, Romanesque, classical antiquity or African cultures that fascinated him so much.

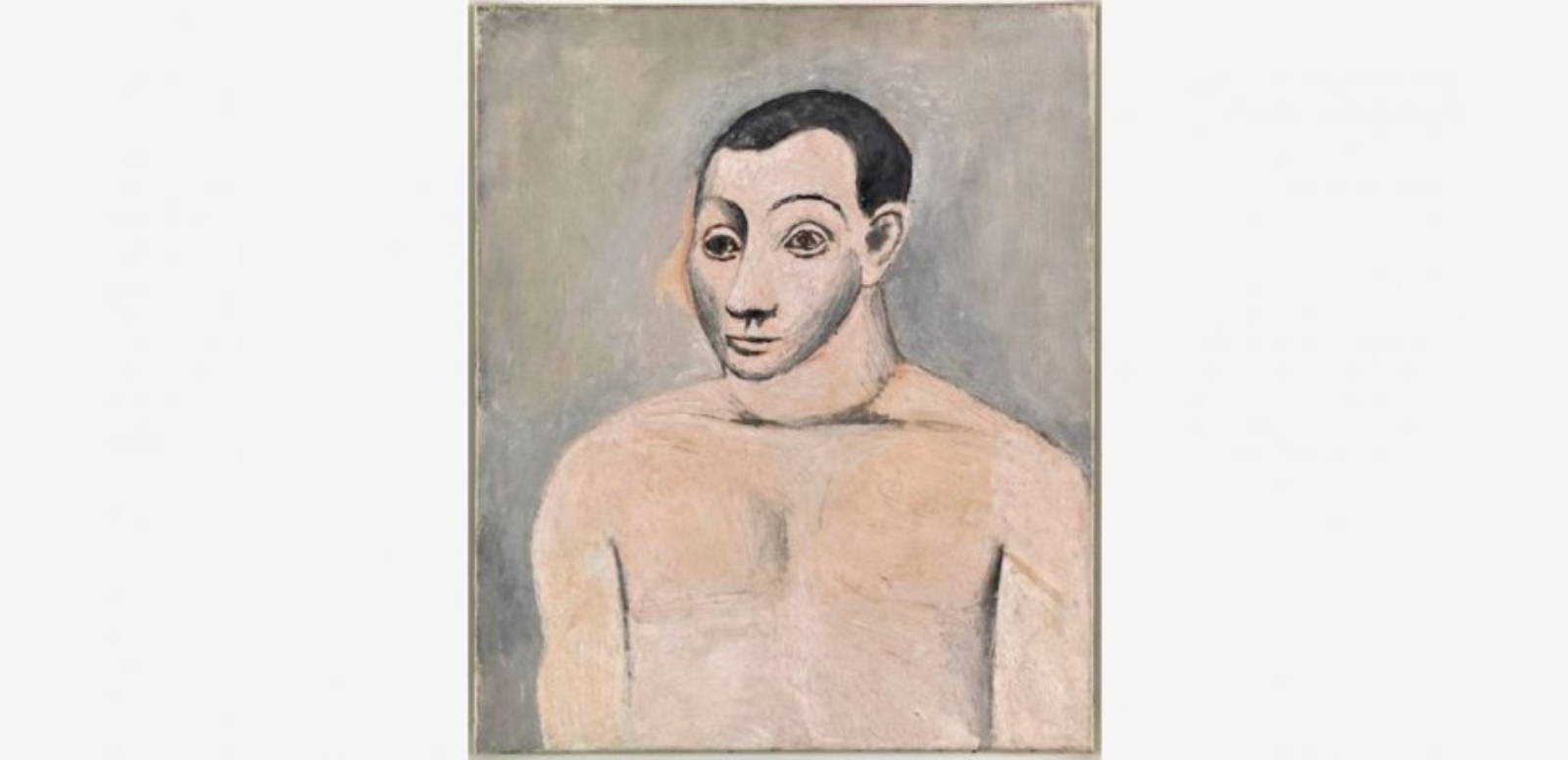

The thesis of the appointment, in principle, would seem innocuous, but soon the sparks begin to fly. It is a matter of highlighting a specific year, 1906, in the evolution of the Malaga-born artist; of studying it, in fact, as another period in his biography with its own entity, not as an epilogue to the 'Pink Period', nor as a prologue to 'The Young Ladies of Avignon' (actually 'young ladies' of Avinyó Street, in Barcelona), where all art manuals place the birth of modernity, via cubism, if one enters through Picasso's door.

It is worth remembering that in that year the young painter spent time with his partner of the moment, the aforementioned Fernande, in the Catalan town of Gosol, another of the Gordian knots of the passage to modernity of the author, so that is where the first headline would start: a soufflé, that of Gosol, which is lowered, because the germ of what would be the avant-garde break was not just a 'summer love' (never better said in this case). Even so, the tour will bring him a room, small, the things as they are, to this stay not so of isolation. And to defend his thesis, the curator relies on two concepts, one of them, the one that lights the fireworks: on the one hand, the sense of transculturality (a hoop that other fathers of the avant-garde such as Matisse or Cezanne did not have to jump through); that notion of the Andalusian emigrated to Barcelona who then travels to Paris and who becomes a "désaxé" (again Fernande) or 'off axis', receptive to the other, to change, and who connects not only with his re-readings of great masters of art (El Greco, the most obvious, with a San Esteban in the Prado that is a delight; also more contemporary, such as Corot, whom he collected, and with a stellar appearance in the exhibition), but also with his appropriation of ancient art (Western and African) not with the eyes of an anthropologist, but looking for the 'koiné', a common origin to all cultures.

And, on the other hand -and this is where the rivers of ink begin to flow-, an unusual attention to the body (a modern concept, also because of the performative aspect it entails) and not so much to the nude (a term of 19th century art) that for Carmona connects with realities of the time with which our protagonist flirted, such as libertarian anarchism (also nudist). And Fernande, again, will recall Picaso's taste for working naked; for practicing nudism with his guests; for rejoicing with his "Andalusian feet"); Freud's new theses on sexuality and -tachán!- the first German homoerotic magazines of bodybuilders at the beginning of the century. By the way, in a museum as given to the 'papelito' as the Reina (and given that this is a quote inherited from Borja-Villel) one misses some copies in the room, more than anything else, to reinforce the thesis. We will have to be satisfied with the photos of Wilhelm von Gloeden and the ephebes of the Archaeological Museum of Cordoba.

Don't panic!

Don't panic! Neither Picasso was gay, nor bisexual, nor 'fluid gender' (although his harlequins and acrobats are, according to Apollinaire, or, as the curator explains, "there are many university studies in the U.S. that analyze his work in this key". The curator explains that "there are many university studies in the U.S. that analyze his work in this key"), but rather the intention is to emphasize a certain homosexual circle with which he surrounded himself (Whilhelm Uhde, his first dealer; Max Jacob or Gertrude Stein -and what a marvel his MoMA portrait that we now enjoy in Madrid, another of those milestones surrounded by the legend of 1906! Apollinaire...), without which Picasso would not have been Picasso.

In short: that modernity -to him- has been inevitably crossed by a certain influence of homosexuality, which, according to Carmona, in Picasso will not be "an exception, but a category". With a final coda and the fall of the audience: Modernity was 1906 and 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon', a return to order. Fade to black.

Carmona is not a newcomer to Picasso's affairs, and his theory is supported at all times by others (Cristoph von Tavel, Rober Lubar, Robert Rosenblum, Linda Nochlin...) who have been considering the matter since the nineties. Be that as it may, it is worth approaching this event with clear eyes (even Carmona admits that maybe Apollinaire was blinded by passion), without homophobic and misogynist jackets (the usual) or waving rainbow flags (in which a good part of universal art is wrapped, from Michelangelo to Warhol and beyond, but that's another story).

This is the only way to enjoy 120 magnificent works and eight sections with Picasso's advances: the use of the body as representation; his fuion of the everyday and the divine; of modernity with the 'primitive'; the new ways of relating form and background and, therefore, of eclipsing the Renaissance perspective; his sculpture that, by the treatment of the material, is 'made' before our eyes; the mixture of high and low culture; how Picasso, of slow digestion, eats and regurgitates ... Something was brewing. Clean look not to miss it. You will come out a winner.