© Sucession Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

The 50 exhibitions organized to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death, which have placed an ecstatic emphasis on the artist, have ranged from the horrendous to the excellent.

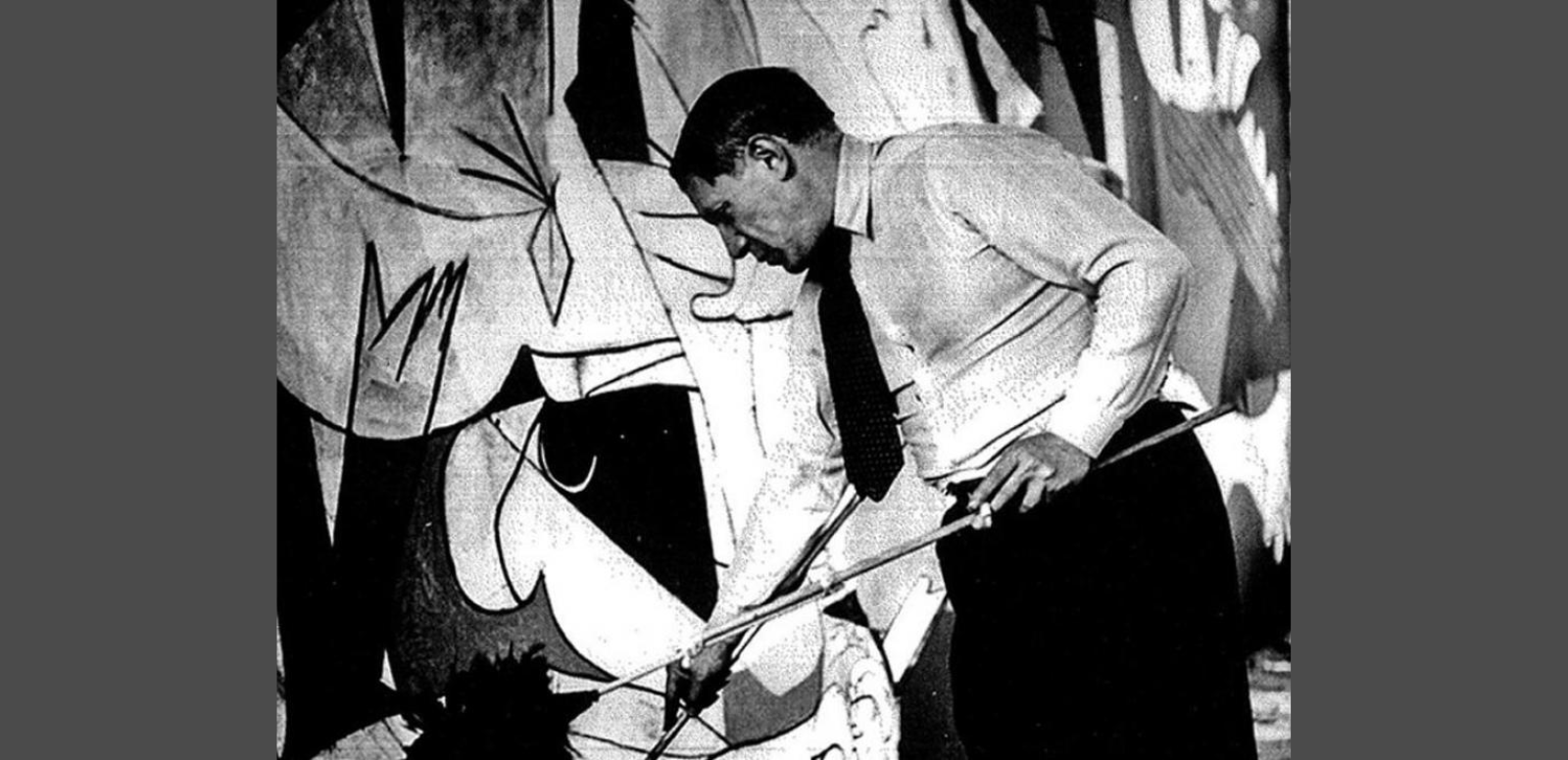

As the decades go by, the figure of Picasso goes from having the measure of genius to that of a legendary man, the latter concept enigmatic, murky, for to the legend of the hero of modernity are added other conjectures, even fabulations, depending on the cultural epochs, but that is also what feeds the character with tension. Fifty years after his death, museums all over the world have celebrated the great transformer of 20th century painting, the eccentric (off axis) and foreigner (for life, in France), the vernacular and transcultural artist, the shaman and the one who, unlike Miró, never intended to assassinate painting but to exploit it to the last of its possibilities.

Bataille commendably expressed it when he referred to his paintings as "horrendous". In an article entitled Putrid Sun, he celebrated the Picassian decomposition of the sun: "The same sun that symbolizes elevation, formal achievement, the unity and productivity of a culture, is an inherently violent and wasteful sun. That sun at its zenith, the most blinding, is the one we get to see by exposing ourselves to danger." Picasso continues to be that plausible light in tributes, exhibitions, seminars, essays. Flashes that sometimes illuminate us or cast us as shadows, because we know that the sun escapes a definitive, privileged vision. From some exhibitions, we come out enriched, capable of absorbing his painting in another paradigm of values; from others, dispossessed, because sometimes the curator is the obstacle.

The one that can be seen until January 7 at La Casa Encendida, in Madrid, can be described as splendidly horrendous -and here it is necessary to be literal-. Splendid for the volume of pieces from the artist's last decade, but horrendous for the logic of simulation it proposes. Picasso: Untitled is in charge of Eva Franch and is more of a dissuasive artifact than an exhibition. It is made up of 50 works re-titled by 50 contemporary artists, confusingly arranged in two almost dark rooms, saturated with neon lights, mirrors, loose posters and platforms decorated with borrowed phrases, lucubrations and reproaches to the honoree.

From superficiality to substantiation there are a few steps, and they take us to the Reina Sofia, where Eugenio Carmona signs an exhibition (until March 4) whose cause lies in the alteration produced in Picasso's work and, by extension, in modern art, in 1906, l'année du grand tournant, the year before Les demoiselles d'Avignon. His thesis is not unpublished, but it allows us to add readings in the current light, such as the "emergence of the body as meaning" in the paintings that Picasso created in the Lleida village of Gósol, the painter's open relationship with homosexuality, the slippage of gender in the popular iconography that the artist observed in the circus rings and fairgrounds, which during those years were his spécialité. Carmona sums it up in the statement that the painter "worked dialectically between his own linguistic development and the synergy with the koiné of the primitive". The idea may sound complicated, but translated into the 120 works that comprise it is a visual spectacle.

Another highlight is the Miró-Picasso double exhibition (Museu Picasso and Fundació Miró, in Barcelona, through Feb. 25), which illustrates the long history of complicity and mutual admiration of two innovative spirits, through paintings, sculptures, books and links with Barcelona, as well as offering the opportunity to see pieces that hardly travel, such as the curtain for the ballet Mercure (1924), or to see confronted their respective "screams", Flame in Space and Naked Woman (1932) and Great Nude in a Red Armchair (1929). At the Thyssen Museum, The Sacred and the Profane is based on the eight works by Picasso from its collections plus some loans, and is curated by Paloma Alarcó, under the not new assertion that the artist conceives "his own capacity of creation as a manifestation of a magical power".

The Picasso Year thus closes an estimable program of 50 exhibitions, 16 of them in Spain and the rest abroad, with diverse looks, from historicist (Cubism and the tradition of trompe de l'oeil, at the Metropolitan in New York) and biographical (Fernande and Picasso in the Bateau-Lavoir workshop, in Paris) to penetrating analogies (Picasso/Poussin/Bacchanales, in Lyon). All of them have placed an almost ecstatic emphasis on the artist, although they have also enunciated an interesting idea, however disturbing it may seem to us: that such a prolific author is as much a process as a person. The real contribution of the ephemeris -and this is the novelty that carries with it a promise of revisiting the character and his work- is the recent creation of the Picasso Study Center at the Picasso Museum in Paris, a space dedicated to research that brings together a documentation space, a library and the museum's archives, the repository of the first Picasso collection in the world. It seems that the great architect of modernity will also tell us how we should remember.